You're at the range, putting five shots into a ragged hole at 600 yards. Your rifle's dialed in, your ballistic app is spot-on, and you're feeling confident. Then opening day arrives, and that bull elk is standing broadside at 650 yards across a canyon. Do you take the shot?

This is where the rubber meets the road in long-range hunting ethics. It's not about what you can do on paper targets or steel plates. It's about what you should do when there's a living animal in your crosshairs and no second chances.

Here's the thing: long-range hunting isn't inherently unethical, but it's not automatically ethical either. The line isn't drawn at 300 yards or 500 yards or any arbitrary distance. It's drawn by your skill, your equipment, the conditions, and most importantly, your honest assessment of whether you can make a clean kill.

What actually defines "long range"

Let's get one thing straight — long range means different things to different hunters. For a guy with a .30-30 and iron sights, 150 yards might be pushing it. For someone with a precision rifle and quality optics who practices regularly, 400 yards might be routine.

The industry likes to throw around terms like "extended range" and "extreme long range," but these are marketing categories, not ethical boundaries. What matters is your personal effective range — the distance where you can consistently place shots in the vital zone under field conditions.

I've seen hunters who think buying a $3,000 rifle system automatically makes them long-range capable. They'll zero at 100 yards, maybe shoot a few groups at 300, then head to the mountains thinking they're ready for 600-yard shots. That's not how this works.

Your effective range isn't determined by your rifle's capability or your best group on a calm day. It's determined by your worst acceptable performance under hunting conditions. If you can shoot 1 MOA groups at the range but struggle to keep shots in a 6-inch circle when you're breathing hard after a climb, your effective range just got shorter.

The military defines long-range differently than hunters do, and for good reason. They're shooting at targets that shoot back, often from prepared positions with spotters and rangefinders. We're shooting at animals that deserve a quick, clean death. The standards should be higher, not lower.

The skill gap between range and field

Range shooting and hunting are different sports. On the range, you've got a stable bench, known distances, consistent lighting, and all the time in the world. In the field, you're shooting from awkward positions, estimating ranges, dealing with wind you can't see, and your heart rate is probably through the roof.

I learned this the hard way on a mule deer hunt in Colorado. I'd been shooting sub-MOA groups at 500 yards all summer, felt completely confident in my setup. Opening morning, a nice buck stepped out at what I ranged as 475 yards. Perfect broadside shot, no wind, solid rest on my pack. I sent the shot and watched the buck run off unscathed.

What went wrong? Everything that could. The angle was steeper than I thought, throwing off my range calculation. I was breathing hard from the climb and didn't settle down properly. The morning light created shadows that made the deer's vitals harder to define. All those range sessions didn't prepare me for the variables I'd face in the mountains.

That's why your practice needs to match your hunting. If you're going to take long shots, you need to practice long shots under field conditions. Shoot from hunting positions — prone with a bipod, sitting with a pack rest, kneeling against a tree. Practice in different light conditions, at different angles, after physical exertion.

Most importantly, practice with a shot timer or have someone call your shots. In the field, you rarely get unlimited time to set up the perfect shot. The animal might move, the light might change, or another hunter might walk into the area. If you can't make the shot within 30 seconds of getting into position, you probably shouldn't take it.

Equipment that actually matters

Long-range hunting puts different demands on your gear than target shooting. You need equipment that's reliable, repeatable, and works in field conditions. That doesn't always mean the most expensive option.

Your rifle needs to shoot consistently, not just accurately. A rifle that shoots 0.5 MOA on a good day but opens up to 2 MOA when the barrel heats up isn't a long-range hunting rifle. You need something that maintains accuracy across multiple shots and temperature changes.

The scope is where most hunters get it wrong. They'll buy a rifle that costs twice what their scope costs, then wonder why they can't make consistent hits. For long-range work, you need clear glass, reliable tracking, and enough magnification to clearly define your target. But more importantly, you need a reticle system that lets you hold for wind and elevation corrections quickly.

I've used scopes that track perfectly on the test bench but shift zero after a day on horseback. I've had turrets that were precise to the click at the range but bound up in cold weather. Field reliability trumps paper specifications every time.

Your rangefinder needs to work on the animals you're hunting, not just reflective targets. A unit that ranges steel plates to 1,200 yards might struggle to get a reading on a dark animal at 400 yards in low light. Test your gear on actual game animals, or at least realistic targets in hunting conditions.

Ballistic calculators are tools, not magic. They're only as good as the data you feed them, and they can't account for every variable you'll encounter. Use them as a starting point, but verify your drops at actual distances. And always have a backup plan when technology fails.

Field notes: The shot that taught me everything

Three years ago, I had what I thought was a perfect setup on a bull elk in Idaho. The bull was feeding in a meadow 520 yards away, completely unaware of my presence. I had a solid prone position behind my bipod, a clear view of the vitals, and no wind to speak of.

I ranged the bull three times, got consistent readings, dialed my scope, and settled in for the shot. The crosshairs were steady on his shoulder, my breathing was controlled, and I had all the time in the world. Everything felt right.

The shot broke clean, and I watched the bull drop immediately. But something bothered me about the whole thing. It felt too easy, too clinical. I realized I'd been so focused on the technical aspects — the range, the ballistics, the equipment — that I'd lost sight of what I was actually doing.

That bull died quickly and cleanly, which is what matters most. But the experience made me think about the relationship between hunter and prey, about the skills that define hunting versus shooting. There's nothing wrong with using technology to make ethical shots, but there's a point where the technology becomes the primary skill, not just a tool.

I still take long shots when the situation calls for it, but I've become much more selective about when and why. The question isn't whether I can make the shot — it's whether I should.

Common mistakes that wound animals

Most long-range hunting failures come from the same handful of mistakes. These aren't equipment failures or bad luck — they're judgment errors that can be avoided with honest self-assessment.

Overestimating your ability under pressure. Your best range performance isn't your hunting standard. If you shoot 1 MOA groups at the range, assume you'll shoot 2 MOA in the field until proven otherwise. Build in a margin for error, because there will be errors.

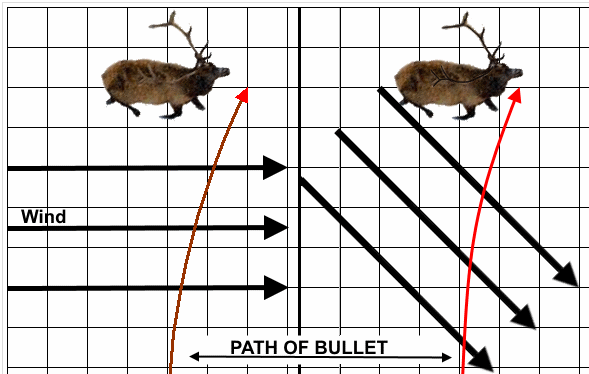

Ignoring environmental factors. Wind is the biggest variable in long-range shooting, and it's the hardest to read. A 10 mph crosswind that you can't feel can push a bullet 8 inches off target at 500 yards. Learn to read wind signs — grass movement, mirage, dust — and when in doubt, get closer or pass on the shot.

Taking shots at moving animals. This should be obvious, but I've seen hunters attempt 400-yard shots on walking deer. Unless you've practiced extensively on moving targets at long range — and most hunters haven't — stick to stationary animals. A wounded animal that runs off is worse than no animal at all.

Shooting at poorly defined targets. Long range magnifies everything, including your ability to misjudge anatomy. If you can't clearly see the vitals and define your aiming point, you're not ready to shoot. Shadows, brush, and poor light can all create situations where a shot looks good through the scope but isn't.

Rushing the shot. Just because you have a long-range setup doesn't mean you need to use it immediately. Take time to assess the situation, confirm your range, check for wind, and settle into a solid position. If the animal moves before you're ready, let it go.

When conditions say no

Even with perfect equipment and solid skills, there are times when the conditions make long-range shots unethical. Learning to recognize these situations is as important as learning to shoot.

Wind is the most obvious factor, but it's also the most misunderstood. A gentle breeze at your position might be a howling gale where the animal is standing. Look for wind indicators across the entire bullet path — grass, trees, dust, even the animal's behavior. If you can't read the wind with confidence, don't take the shot.

Light conditions matter more at long range than most hunters realize. Early morning and late evening shots can be challenging even with good optics. Shadows can hide vital anatomy, and backlighting can make range estimation difficult. If you can't clearly define your target and aiming point, wait for better conditions or get closer.

Shooting angles add complexity that many hunters don't account for. Steep uphill or downhill shots require different holds than flat shots at the same distance. Most ballistic calculators can compensate for this, but you need to input accurate angle data. A 30-degree slope can change your point of impact by several inches at long range.

Temperature and altitude affect bullet performance, especially at extended ranges. A load that's zeroed at sea level will shoot differently at 8,000 feet. Extreme cold can slow your powder, while extreme heat can increase pressure. If you're hunting in conditions significantly different from where you practice, verify your zero and trajectory.

The practice that actually prepares you

If you're serious about long-range hunting, your practice needs to be serious too. Shooting groups off a bench at known distances is a start, but it's not enough. You need to practice the skills you'll actually use in the field.

Start with position shooting. Learn to shoot accurately from prone with a bipod, sitting with a pack rest, and kneeling with sling support. Practice getting into these positions quickly and settling in for the shot. Time yourself — if you can't get stable and break a good shot within 45 seconds, you need more practice.

Practice range estimation without a rangefinder. Technology fails, batteries die, and sometimes you don't have time to range your target. Learn to estimate distances using the mil-dot or hash marks in your scope reticle. Practice on objects of known size until you can consistently estimate ranges within 5% at hunting distances.

Shoot in different weather conditions. Wind, rain, snow, and temperature extremes all affect your shooting. If you only practice on calm, sunny days, you're not prepared for hunting conditions. Some of the best hunting happens in marginal weather.

Practice shot calling. Learn to read your natural point of aim, follow through, and recoil pattern. A good shot feels different from a bad shot, and experienced shooters can often tell where their bullet went before looking through the scope. This skill can save you from taking follow-up shots on animals that are already hit well.

Most importantly, practice with consequences. Set up realistic targets at unknown distances and give yourself one shot to hit the vital zone. Miss, and you're done for the day. This builds the mental discipline you need when there's an animal in your crosshairs.

Rifle and cartridge considerations

Not every rifle is suitable for long-range hunting, even if it shoots well at the range. Hunting rifles need to be reliable, consistent, and capable of delivering sufficient energy at extended ranges. They also need to be practical to carry in the field.

Your rifle needs to maintain accuracy as the barrel heats up. A rifle that shoots sub-MOA cold bore shots but opens up to 2 MOA after three rounds isn't suitable for long-range hunting. You might need follow-up shots, and your zero might shift during a long day of hunting.

Barrel length affects velocity, which affects trajectory and energy downrange. Shorter barrels are handier in thick cover but give up velocity that you need for long-range performance. For most long-range hunting cartridges, 24-26 inches is a good compromise between velocity and handling.

The stock needs to fit you properly and provide a stable shooting platform. Adjustable combs and length of pull help you get consistent scope alignment, which is critical for long-range accuracy. A stock that fits well will also help you shoot more accurately under stress.

Cartridge selection matters, but not as much as most hunters think. A .308 Winchester with good bullets will kill elk cleanly at 500 yards, while a .300 Ultra Mag won't make up for poor shooting skills. Choose a cartridge you can shoot accurately and that delivers sufficient energy at your maximum range.

Energy requirements vary by game species and shot placement. A broadside lung shot requires less energy than a quartering shot through heavy bone and muscle. As a general rule, 1,000 foot-pounds of energy is minimum for deer-sized game, 1,500 for elk-sized game. But shot placement trumps energy every time.

Bullet performance at distance

Bullet selection becomes critical at long range. You need projectiles that retain velocity, resist wind drift, and expand reliably at lower impact velocities. This usually means high-ballistic-coefficient bullets designed for long-range performance.

Traditional cup-and-core bullets often don't expand reliably at the lower velocities you get at extended ranges. Bonded bullets and monometal designs typically perform better, but you need to verify expansion at your expected impact velocities. Some bullets need 2,000 fps to expand properly, others work down to 1,600 fps.

Ballistic coefficient affects both trajectory and wind drift. Higher BC bullets drop less and drift less in the wind, making long-range shots easier. But BC is only part of the equation — you also need bullets that shoot accurately in your rifle and perform on game.

Match bullets can be extremely accurate, but they're not designed for hunting. Some work fine on game, others fragment or fail to expand. If you're going to use match bullets for hunting, test them thoroughly and understand their limitations.

Bullet weight affects both trajectory and terminal performance. Heavier bullets typically have higher BCs and retain energy better at long range, but they also have more drop. Lighter bullets start faster and shoot flatter, but they lose energy more quickly. There's no perfect answer — it depends on your specific needs and rifle preferences.

Technology as a tool, not a crutch

Modern technology can make long-range hunting more effective and more ethical, but only if you understand its limitations. Rangefinders, ballistic calculators, and weather meters are tools that supplement your skills, not replace them.

Rangefinders can fail, give false readings, or be impossible to use in certain conditions. Learn to estimate ranges using your scope reticle and natural references. Practice until you can get within 5% of the actual distance consistently.

Winchester .308 Winchester Deals

Prices may change. May contain affiliate links.

Ballistic apps are incredibly useful, but they're only as good as the data you input. Garbage in, garbage out. Verify your actual drops at multiple distances and adjust your app accordingly. Environmental conditions can change throughout the day, affecting your trajectory.

Weather meters can provide precise wind speed and direction readings, but they only tell you what's happening at your location. Wind can be completely different where your target is standing. Learn to read wind signs across the entire bullet path.

GPS units and mapping apps can help you plan shots and recover game, but don't rely on them exclusively. Batteries die, signals get blocked, and technology fails at the worst possible times. Always have backup navigation methods and tell someone your hunting plan.

The best technology is the technology you understand completely and have tested thoroughly. If you can't use a piece of equipment quickly and confidently under stress, leave it at home. Simple, reliable tools that you know well are better than complex systems you don't understand.

The ethics beyond the shot

Long-range hunting ethics extend beyond just making the shot. You have responsibilities before, during, and after pulling the trigger that become more complex at extended ranges.

Before the shot, you need to honestly assess your capabilities and the conditions. This means being realistic about your skills, understanding your equipment's limitations, and recognizing when conditions make a shot inadvisable. It also means having a plan for recovering the animal if your shot placement isn't perfect.

During the shot, you need to be absolutely certain of your target and what's beyond it. At long range, this becomes more challenging. Make sure you can clearly identify your target as the animal you're licensed to harvest. Be aware of other hunters, livestock, or property that might be in your bullet's path.

After the shot, you have an obligation to recover the animal regardless of how far you have to track it. Long-range shots can result in longer tracking jobs, especially if your bullet placement isn't ideal. Be prepared with proper tracking equipment and the physical conditioning to follow a blood trail for miles if necessary.

You also need to be prepared for the possibility that your shot wasn't as good as you thought. Have a plan for follow-up shots, know how to approach a wounded animal safely, and understand when to back off and give an animal time to expire.

What the future holds

The long-range hunting debate isn't going away. Some states are considering distance restrictions, while others are embracing technology that makes extreme-range shots possible. The hunting community needs to police itself before outside forces make decisions for us.

Wyoming has considered legislation that would limit shots to 600 yards on public land. Other states are watching to see how this plays out. The concern isn't necessarily about ethics — it's about wounded animals, hunter conflicts, and public perception of hunting.

The technology will continue to improve. Rangefinders are getting more accurate, ballistic calculators more sophisticated, and rifles more precise. But technology doesn't make hunters more ethical — it just gives them more capability. With that capability comes responsibility.

Hunter education programs are starting to address long-range hunting specifically, teaching both the technical skills and the ethical considerations. This is a positive development that should be expanded. Too many hunters are attempting long-range shots without proper training.

The hunting industry has a role to play too. Marketing that emphasizes extreme range over ethical hunting does the sport no favors. Manufacturers and media outlets need to promote responsible long-range hunting practices, not just the latest gear that can reach out further.

Drawing your personal line

Ultimately, you have to draw your own ethical line based on your skills, equipment, and hunting situation. This line isn't static — it should change based on conditions, your experience level, and the specific hunting scenario.

Start conservative and expand your range gradually as your skills improve. There's no shame in passing up shots that other hunters might take. In fact, knowing when not to shoot is often the mark of an experienced hunter.

Practice regularly and honestly assess your performance. Keep a shooting log that tracks your accuracy under different conditions. If your groups are opening up or your hit rate is declining, back off your maximum range until you can get back on track.

Consider the specific hunting situation. A shot that might be ethical on a large, open meadow might not be appropriate in thick timber where recovery could be difficult. Factor in the terrain, the weather, your physical condition, and the time of day.

Be willing to adjust your standards based on the game you're hunting. The margin for error on a large elk is different than on a small deer. A shot that would be quickly lethal on one species might not be on another.

Remember that hunting isn't just about harvesting animals — it's about the entire experience. Sometimes the most memorable hunts are the ones where you chose not to shoot, where you got close enough to observe the animal's behavior, or where you learned something new about yourself or the woods.

The line between ethical and unethical long-range hunting isn't marked by distance. It's marked by your honest assessment of your ability to make a clean, quick kill under the specific conditions you're facing. Draw that line conservatively, respect it absolutely, and be willing to let animals walk away when the shot isn't right.

That's not giving up — that's hunting.